INCREASING LANDSCAPE FUNCTION WITH FERTILITY BUILDING TREES ON FARMS

We all know that trees offer shade and shelter on farms, but evidence is showing the many additional benefits of including a variety of trees and shrubs in revegetation plans.

Recently published case studies by regenerative agriculture organisation, Soils for Life, demonstrate that revegetation in a variety of landscapes lifts on-farm production and has environmental benefits, ranging from animal productivity improvements to soil protection, water retention and provision of ecological habitat.

The design of farm revegetation is crucial and should fit the location and the needs of the farm. It’s easy to find local wind breaks and shelter belts that are ineffective, and that don’t build hydration, fertility and production in the landscape. A lot of the tree lanes and rows are short lived, only reaching 10 to 15 years on average, while longer-lived monocultures of pine trees only increase your chances of attracting fire to your farm.

The biggest factor for success is the size of a tree system, especially the width. Look at any tree lanes on any rural road and you will see that they are only five metres wide at maximum. Much of the information available about trees on farms does not show an understanding of what constitutes a tree system and its function. I’m going to challenge traditional wisdom here: what is prescribed as the best trees and shrubs to plant borders on revegetation absolutism, where all plants must be native and endemic to the areas planted.

Organisations and governments are funding revegetation works for wind breaks, stock shelter and riparian areas. I would like to open up the discussion to go well beyond that paradigm, and shift the thinking to tree systems in this article and expand into the specifics in future articles of how to design, install and maintain them.

Tree systems, unlike tree rows and lanes of old, are dynamic in the interactions on the landscape. A tree system must provide multiple functions if it is to succeed.

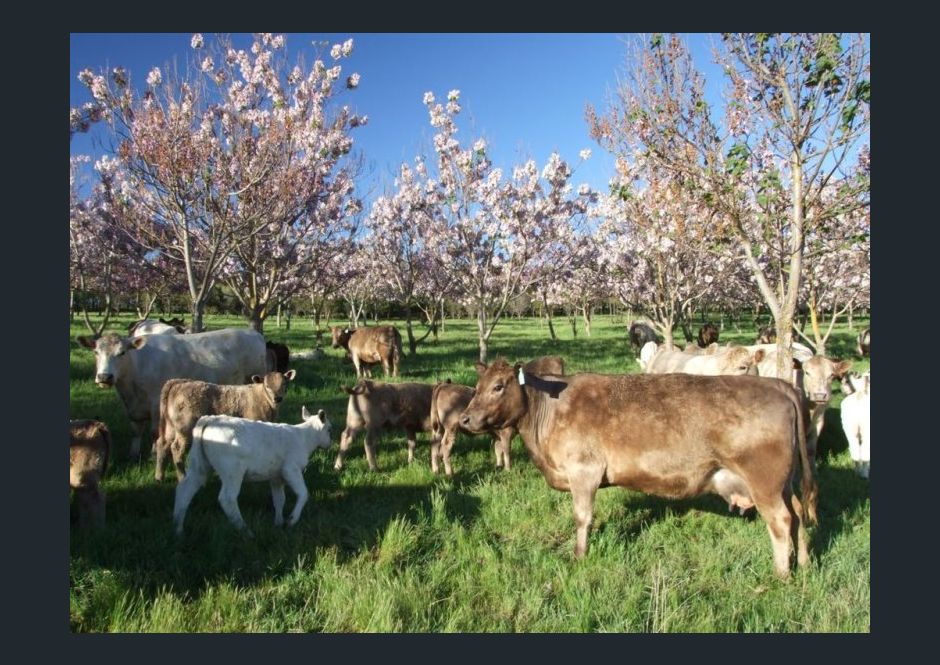

When I’m designing tree systems for clients and Landcare groups I’m projecting a full 50 to 100 years in time. What will these tree systems need to provide in the future for our current forms of production or new forms of agricultural production? What will the level of succession need to be in the tree species over that time to to establish a self regenerating system? Every tree system must provide multiple functions and its functions may include things like wind protection from multiple angles for stock, pasture and crops, stock shade and protection from cold, snow and heat, stock tree fodder, inter-tree grazing, fire protection (more on that in future articles), fertility building using trees that have massive leaf drop and are easily broken down into soil by microbes, increasing soil carbon, harvesting water and infiltrating rainfall quickly, de-compacting hard soil layers with aggressive root systems, increasing soil biology and mycology (fungi), increasing beneficial insect and bird habitat, wildlife interactions, firewood, fence posts, and saw log timber. That might be quite wish list but its no pipe dream. Thoughtful creative design can deliver these outcomes.

Importantly, the minimum width of tree systems is 30 metres and they must include almost no eucalypts.

What trees can do all this?

I look for trees that will not only grow but that will thrive in the local landscape and climate. I aim for a mix that are that are nitrogen fixing, bird and insect attracting, have evergreen and deciduous seasonal leaf drop, are fruit or nut bearing for animal and human consumption, produce pollen and nectar at different times of year, have deep roots and shallow fibrous roots, and cycle water and nutrients.

In the past eight months out at Jacmarall Farm near Tarago NSW we have been planting mixes of trees from English to red oaks, poplars and acacias as nitrogen fixers and pioneer trees. We also plant pine trees—yes pine trees—in small interspersed tree systems as fast-growing protection for smaller trees. Our latest additions are evergreen oaks, and native bunya pines that will produce food for future families in the form of carbohydrates from their 20 kg cones. In these diverse tree systems, as the acacias cycle through and die out, fruit trees and animal fodder trees will be planted in their place. In our nursery growing now are tree lucerne, native she-oaks and old man saltbush that will all become stock fodder in the future. Two tree systems established in the past two years are 30 metres wide and 300 metres long. At this size they will become new future paddocks as sensitive trees get above the browse line of cattle and sheep. The acorns from oaks will become an optimal food source for our pastured pigs to graze on.

WHY EXCLUDE EUCALYPTS?

Ive just finished reading Recreating the Country by Victorian nurseryman Stephen Murphy. This very well researched book focuses on creating Australian native landscapes on farm lands, perfect if you’re looking to bring back the native bush to your land but not so much if you want to graze exotic animals on exotic pastures and increase fertility as we have described above. And here’s why: On page 38, the author makes the claim while stating how to establish the ground cover layers (as trees in his tree systems increase in hight) “The soil conditions also change because of competition from the taller vegetation (Eucalyptus). As the plantation develops, soil moisture and nutrients become more scarcer[RD1] , which suits the harder native grasses—although the soil becomes more porous allowing rainfall to infiltrate more effectively. The exotic annuals and even the tougher perennials like phalaris eventually loose control of the ground layer.”

So while farms lose more and more fertility, we now need to plant those trees that help us lose even more productive soil and moisture[RD2] ? These are not the kind of tree systems I need. I need tree systems that build soils and increase farm production. When you see plantations like the photo below where gums choke out any ground cover and exclude a healthy soil surface then we need to rethink our approach. I’ve planted plenty of gums on Jacmarall farm, just very far and few between—a ratio of one gum to 60 productive trees.

WHY TRADITIONAL WIND BREAKS DON’T WORK

They’re just too small, full stop. Don’t take my word for it, look over the fence at any tree lane or wind break and you’ll soon see they are dying because of a failure to design the system and think into the future. They are only a short-term fix to past land clearing. Farmers that I meet from time to time want to give up as little land as they can. Science has discovered to make the perfect compost pile (one that will heat up to the desired temperature of 65-75 °C) the compost pile needs to be 2 metres wide by 2 metres tall and have the correct ratio of carbon (dry materials), nitrogen (hot materials) and moisture to light the biological oven of good compost. Smaller than that it won’t heat up. Bigger than that and it will heat up too much and cook the inside layers and make the compost unusable. Its the same with tree systems; there is an ideal size for maximum and multiple functions.

Another factor to this is locking out animal interactions or periodic grazing by stock. This needs to be well managed like any grazing system but in our climate of the Southern Tablelands, once stock are excluded from interactions with grasses and soils that area can start to degenerate and we start to lose grasses and soil. Grasses have evolved with herbivores and need periodic ‘hair cuts’ to excite them into new growth and recovery.

When looking at your own property, remember that reasons and approaches to revegetation depend on your own context and management objectives. It’s important that these are clearly understood.

Revegetation, when part of a holistic management approach, provides production, soil health and ecological benefits that cannot be separated from each other.

In future articles I will discuss in more detail how tree systems function. We will look at design, implementation and management of these systems. In the mean time if you have any questions, insights or feedback leave a comment below.

Written by Nick Huggins from Regenerative Landscapes Australia – www.rlaustralia.com.au – Editing by Robyn Diamond – Permaculture Designer and Practitioner